07. June 2017

by Harald Störrle | 1350 words | ~7 min read

Everybody talks about code quality, so surely we have a good understanding of what good (or bad) code is, exactly. Right?

Well, no. There are certainly many books and scholarly articles on the topic, but they present a wide array of different, and often conflicting views. It doesn’t get better if you turn to industry: If you ask three professional programmers, you get four different opinions, and they’re often fuzzy and apply only to the kind of software the programmer is experienced with.

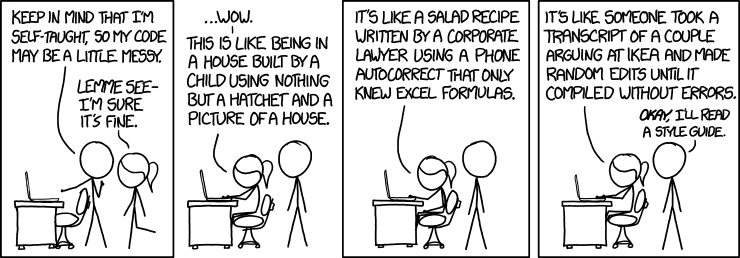

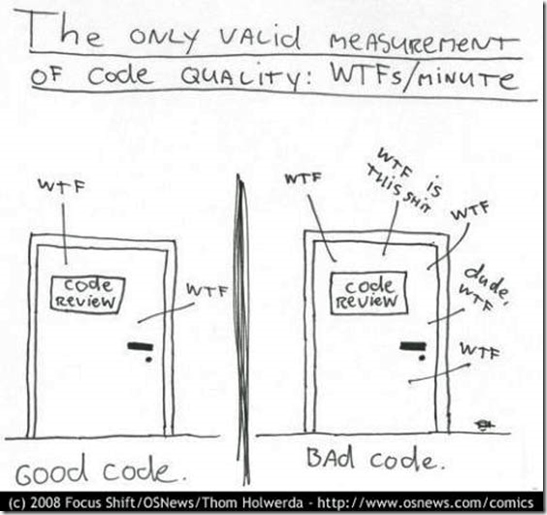

All attempts to come up with a simple and crisp definition that everybody accepts have failed. In the end of the day, people will resort to “I know it when I see it”. Unfortunately, that doesn’t quite cut it, neither from a scientific point of view, nor from a practical point of view.

Some software engineers might be tempted at this point to simply say “Not my problem” and turn away. However, consider the following two scenarios where this lack of a good definition truly is your problem. First, imagine a teaching environment, be it a secondary school or a university, and keep in mind that today’s students are tomorrow’s engineers so they will be your colleagues in no time. In any such setting, students expect to be told what is good code, and what isn’t. After all, that definition will surely affect how their work is graded. Therefore, the definition should be simple, universal, and easy to apply. However, there is a tension between simplicity and universality: simple solutions often fail in difficult situations. That is why practitioners often reject textbook definitions of code quality as simplistic, or vague.

Now imagine a second scenario of a professional programmer acquainting herself with a piece of existing code. In order to understand the code, an IDE can provide valuable help by flagging suspect code to guide the programmer’s attention. Clearly, providing metrics (and threshold values) that the IDE should implement requires absolute precision in the definition of code quality. Without the necessary underpinnings, the tools will be of much less help, to fewer people.

However, the problem is not a shortage of definitions, concepts, and tools – quite the opposite, and all of them claim to be just the right thing, naturally. What we need is guidance to select our approach, lest we want to waste our energy and enthusiasm on ineffective ways or outright hoaxes (and yes, that happens a lot). Unfortunately, there is precious little evidence to help along the way.

In this situation, researchers and practitioners from Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, the United States, and Finland teamed up to form a Working Group at ITiCSE (see WG 2), me among them representing QAware. The working group pursues three goals. First, it needs to validate the above observation and thus turn it into fact. Next up, we want to clarify and systematize the existing aspects of code quality to inform the conversation about code quality. Finally, we want to elicit and contrast the views on code quality that teachers, students, and professionals hold, respectively, with a view to deriving recommendations for programming education with a greater practical value.

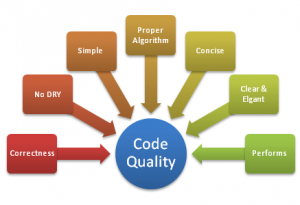

Based on the literature (and common sense), we have some up front idea of what we might find. For instance, we expect to find consistent opinions within groups of people in similar professional situations (i.e., teachers, students, and professional programmers), and different opinions across these groups, simply because they have very different levels of expertise, and are likely concerned with different kinds of quality issues. We expect a progression of levels of more and more global properties.

Clearly, one has to master the lower levels before one can work effectively on the higher levels. But to what degree are the various groups aware of the elements of this hierarchy? Which are the predominant concerns, and what tools and sources of information used by the various populations? And which of the many issues at each level are really relevant, and how do they compare?

There are two types of evidence that exist addressing such questions. On the one hand, there are quantitative studies (mostly controlled experiments and quasi experiments) on very low-level aspects of code quality. Such studies are usually conducted on students and focus on simple metrics1 2 3 4 5, or individual aspects such as readability6 7. Such studies aspire to provide scientific reliability, though necessarily losing ecological validity in the process. On the other hand, there are surveys and experience reports based on practitioner experiences such as 8 9 that generally lack the degree of focus (and, too often, also scientific rigor), but offer a higher degree of validity. Our Study, in contrast, uses a qualitative study design and is the first to look at differences across groups.

Of course, many a practitioner might object that these questions in particular, or even scientific enquiry in general, while interesting, are of purely academic concern. People might often object that science is too slow, and lags behind coding practice and thus is unable to give good guidance for today’s developers. I beg to differ. While I am ready to accept criticisms of science being slow, sometimes wrong, and often not immediately applicable, it is still the only reliable (!) way forward. The IT industry is highly hype-driven, but lasting improvements are rare.

Leaving aside this philosophical argument, I believe questions like the ones addressed in our study offer a set of very practical benefits.

Stay tuned for the initial results of our study due in late June, and follow me on Twitter @stoerrle!

Breuker, Dennis M., Jan Derriks, Jacob Brunekreef. “Measuring static quality of student code.” Proc. 16th Ann Joint Conf. Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education. ACM, 2011. ↩︎

Buse, Raymond PL, Westley R. Weimer. “Learning a metric for code readability.” IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering 36.4 (2010): 546-558. ↩︎

Börstler, Jürgen, et al. “An evaluation of object oriented example programs in introductory programming textbooks.” ACM SIGCSE Bulletin 41.4 (2010): 126-143. ↩︎

Posnett, Daryl, Abram Hindle, Premkumar Devanbu. “A simpler model of software readability.” Proc. 8th Working Conf. Mining Software Repositories. ACM, 2011. ↩︎

Stegeman, Martijn, Erik Barendsen, Sjaak Smetsers. “Towards an empirically validated model for assessment of code quality.” Proceedings of the 14th Koli Calling Intl. Conf. on Computing Education Research. ACM, 2014. ↩︎

Börstler, Jürgen, Michael E. Caspersen, Marie Nordström. “Beauty and the Beast: on the readability of object-oriented example programs.” Software Quality Journal 24.2 (2016): 231-246. ↩︎

Börstler, Jürgen, Barbara Paech. “The Role of Method Chains and Comments in Software Readability and Comprehension—An Experiment.” IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering 42.9 (2016): 886-898. ↩︎

Christakis, Maria, Christian Bird. “What developers want and need from program analysis: An empirical study.” Proc. 31st IEEE/ACM Intl. Conf. Automated Software Engineering. ACM, 2016. ↩︎

Stevenson, Jamie, Murray Wood. “How do practitioners recognise software design quality: a questionnaire survey.” (2016). ↩︎