09. January 2026

by Alexander Krauss | 2287 words | ~11 min read

ide developer tooling coding agents developer experience ai-driven development

We are in the middle of the AI transformation of software development, and I am not able to tell if we are 20% in or already halfway through. But we are clearly going to see some more changes affecting not just tools and models, but also engineering practices and beliefs that we have gotten used to.

I have been watching the evolution of developer tooling for many years, and I find it interesting to see what is currently becoming of the IDE. While the concept of the IDE (Integrated Development Environment) has seen some evolution and an explosion of complexity in the last decades, I would argue that it has not fundamentally changed: Turbo Pascal from the early 90s already had most of the basic concepts from today’s IDEs: a code editor, a compiler, build integration, a debugger. Many other concepts have been added, but they must all fit into the editor-centric world view.

Now, there is a tectonic shift. Let me predict that IDEs are going to change fundamentally. And, of course, the integration of agents in the development process is the driver of this change. Agents edit files, but they do not use editors in the same way. They run and sometimes debug code, but they use different approaches. And they are pervasive and here to stay.

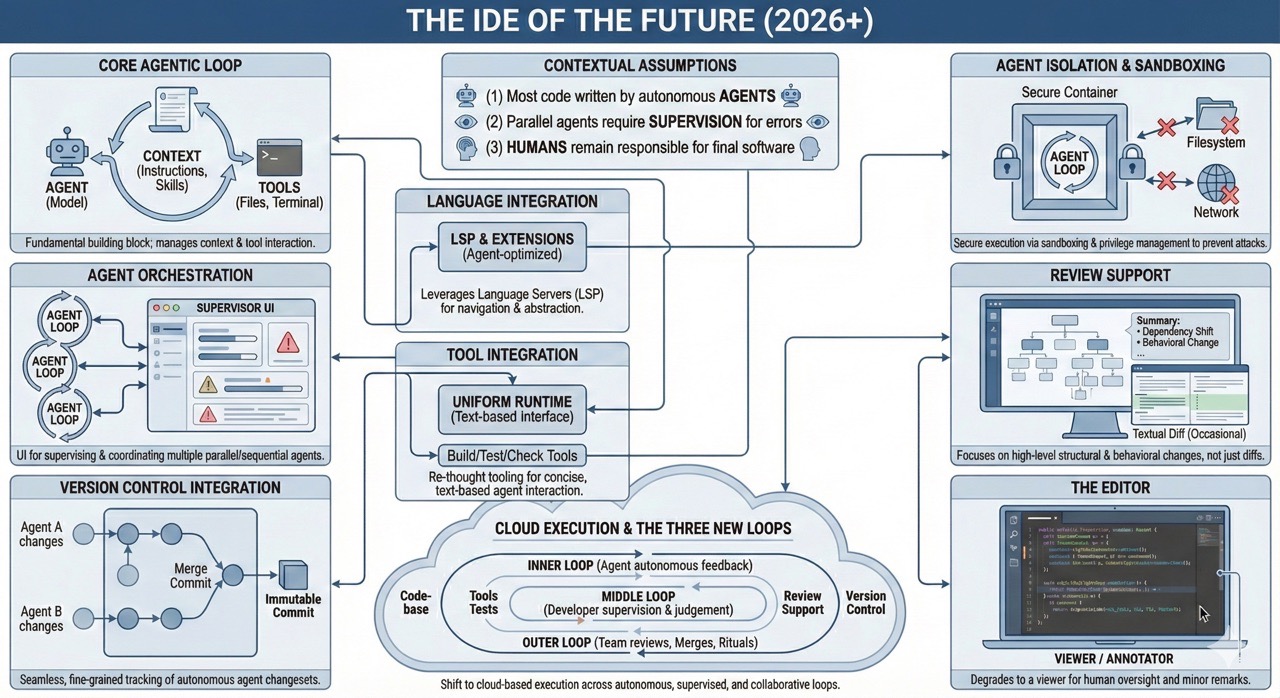

In the following, I want to go through the capabilities that (used to) make up an IDE, and how they are changing. I will make the following assumptions, which look fairly reasonable at the end of 2025:

So let’s have a look:

The editor used to be the one central piece of UI in any IDE. Here is where the code gets created. It has complex forms of syntax and other highlighting to enrich the perception of the user and bring the relevant information into view.

When agents make the majority of the code changes, then the editor degrades to a mere viewer, perhaps with the option to make the occasional small edit or to add a remark.

Agents have seen vast improvements this year, but their fundamentals haven’t changed much. I will therefore assume that the IDE contains or communicates with an agent loop that manages context, conversation and makes files and a terminal available through “tools”. We have seen some changes around context management, such as managing agent instruction files and skills (incrementally discoverable instructions for certain types of tasks). There will probably be further innovations in this area, which allow models to make better use of their limited context.

Must the agent loop be part of the IDE or can it be some other, independent product category? That’s a fair question, but we can turn it around: Can we think of a useful IDE that does not somehow contain an agent loop as a fundamental building block? I think the answer is no. The agent might be connected to the other components via some protocol like ACP, but it will be an integral part of the development tooling.

One agent is only the start of it, and we are seeing many people using multiple agents at once, giving them different tasks, or sometimes the same task. There is currently no good UI for supervising multiple independent (or sequential) agents, and there clearly is a need for that.

Current IDEs would not be complete without at least some integration with git. However, their current workflow addresses mostly manual commits, push/pull and merges. At the same time, many coding agents have invented some form of undo functionality, which is sometimes even built on git but introduces another (primitive, non-branching) notion of history and changes, even though we already have a richer notion available.

Currently, git is dominating the market entirely, but we are seeing notable conceptual simplifications in Jujutsu, which might free us from some baggage once it becomes more popular.

In my imagined IDE, the integration is seamless: When agents make modifications, their modifications are tracked as changesets in every conversation turn, maybe together with their conversation state. This would make their actions traceable and allow a simple way of having branched agent conversations.

Of course, before committing changes into immutable eternity, we will discard some of the fine-grained history and replace it by helpful summaries, just as we do with local editing history. But the formal framework is always the same.

Note that the combination of version control integration and agent orchestration requires some form of isolation between the agents on a filesystem. This is what some people use separate git worktrees for, but it is far from a good experience: When I do this, I want to see all the changes immediately in a revision graph. I want to be able to zoom into what each agent is currently doing, and I want to see the produced changes of each agent in an editor. I want an IDE to support me doing this.

An IDE needs to understand the programming language to allow navigation and contextual editing operations that make use of language abstractions. Early IDEs had to build their own internal abstractions, but recently this has been outsourced to language servers following the LSP protocol. The good thing is that these language servers can probably be reused in the next generation of IDEs.

Agents will also make use of language-specific tools: Some agent tools (e.g., opencode) have had such integrations for some time, and now Claude Code follows, so I guess we will soon see all agents support language servers. I can also imagine extensions to LSP that work better with agents as clients. It is possible that a mature integration of language servers will also require training the models to use these new agentic capabilities better. But it is just hard to imagine a future where basic refactorings are spelled out in terms of atomic edits instead of proper refactoring operations on code.

Integrating the vastly different tools for building, checking, testing, packaging, deploying is the I in IDE. It makes developers productive by combining the various tools into a coherent user interface that is efficient to work with.

This integration must now be re-thought for agents, which prefer text-based interaction over keyboard and mouse. I think there is a chance to re-think these forms of developer tooling in this new light. Some primitives are always the same: watching files and re-building derived artifacts when something changes (where a derived artifact may also be a test report). Adding more information to the source code (e.g. from static analysis or tests). I think we need a uniform runtime for this type of things that can be extended and that is easily accessible for agents.

Also, the tools themselves will need to change. Output should be text-based, well-structured and, above all, concise, to avoid overloading the agent with too much garbage in their context. Right now, I subsume this under the term “agent developer experience”: Tools must be easy to use, provide concise and self-explanatory feedback, and they must be fast, since we will want to run them in closed loops to give feedback to our agents.

Yes, we are going to review software written by agents. But that review will not always be done on a textual diff between two revisions, as it is now common. We will do that occasionally, but our review should first focus on the high-level building blocks, their relationship and how the change affects the structural properties of our software, as well as its behavior as described by tests.

Review on an architectural level is largely unexplored, at least in the industry. How do I summarize code changes concisely (without just blindly resorting to an LLM that might miss or misrepresent changes)? How do I visualize structural changes such as changing the dependencies between modules? How do I show how code was reused and how it was decoupled? I very much hope that there will be innovation in this space, since we will really need it to be able to work on a higher level.

Our new agent reality comes with a strong caveat: Agents are smart and dumb at the same time and susceptible to prompt injection attacks. In particular, the combination of access to untrusted content, the access to code and potentially private data on the development machine and the fact that it is relatively easy to exfiltrate data (this combination has been named the lethal trifecta) make the whole setup very vulnerable. Moreover, the combination of generating and subsequently executing arbitrary code with the privileges of the developer and access to data on their machine is a recipe for disaster.

Currently, there are only two valid approaches. One is to scrutinize every single agent action manually, quickly becomes a new annoying bottleneck and source of frustration. The other approach is to run the agent with minimal privileges and data access possible, by means of sandboxing. We want the agent to have only limited filesystem access to give it the code it needs, but not the other things on the user’s file system such as personal information, API keys, etc. We also want to be able to restrict internet access for the agent, which restricts access to (potentially malicious) data out there and avoids exfiltration vectors.

Since we postulated that the IDE of the future manages and orchestrates agents, it will also need to take care of sandboxing. An agent definition will come not only with instructions and tool definitions but also with access privileges and isolation configuration. We must then reason about the different agent types and their properties to derive security properties of the agentic process.

The most successful coding agents currently run on the developer machine. However, the idea of having an IDE in the cloud is not new. So far it has not really taken off, and I can only try to guess why. The combination of good provisioning latency, a decent machine comparable to a good developer laptop and competitive cost is hard to get right, and moving a traditional IDE into the cloud is also non-trivial.

But when we get into the territory of agents running independently for a couple of hours (research suggests we can expect this when continuing on the current trajectory), then running them locally is no longer practical, and we want to move the process to the cloud, into a well-defined runtime environment which also provides the necessary sandboxing.

Besides technical challenges, this is a conceptual shift: Traditionally, we had a separation of local development running on the developer’s machine and a CI that was running on some server. The move between one and the other was mediated via version control. In a future setting, I see the distinction between local and server disappear. Instead three new loops arise, based on whose attention they require:

The inner loop is run by an agent autonomously. The agent interacts with the codebase and the tools and decides when it thinks it is done. It may also receive automatic feedback by specialized feedback agents and deterministic tools such as tests and linters.

The middle loop is governed by the developer responsible for that particular set of changes. They guide and supervise the agents and make judgement calls concerning design and scope of what to do in that step.

The outer loop affects other team members, typically in the form of reviews, merges, or rituals such as sprint reviews. This is by definition slower.

The IDE of the future must support all three loops, but not dictate the processes used, in particular in the outer loop.

We are seeing some elements of this already, but we cannot download or buy the whole thing as a product just yet. This is just fair, as there are a lot of things to work out and not everything that I can think of when going on a walk will probably be practical. But we see that (1) the product category of an IDE is getting a major update, and it is not at all clear if the existing players (Jetbrains, I am looking at you) can reinvent themselves in order to play a role in the next generation. Neither are agents just yet another IDE plugin that lives in a sidebar. And (2), the IDE will not collapse into a simplistic terminal application as we now now see it everywhere. It remains a complex integration product that combines AI agents, specialized GUIs and system integration.

In such a system, I can imagining opening the revision graph, seeing three running agent branches, each with a diff + tests + budget + permissions; After visualizing the architectural impact and checking that there are no unexpected dependencies, and after noting that the tests cover the properties that I want to see, I promote one branch and squash provenance into a review changeset, which I’ll later discuss with a teammate. I’ll directly push one other branch (an easy change) and abandon the third since it did not match my assumptions. I still learned something from the failed attempt, and I add that learning to my concise spec document that will guide the agent whe restarting another attempt.

I am looking forward to using these new generation of IDEs. In the meantime we’ll have to resort to the individual parts taped together with custom scripts, reusing some pieces of a classic IDE.

Sebastian Macke provided valuable suggestions and thoughts reviewing a draft of this article.