Exploratory software testing is a technique every agile developer should know about. It’s about test driving your application without a predetermined course of action. Although this seems like random free style testing, in the hands of an experienced developer this proves to be a powerful technique to find bugs and undesired behaviour.

But in this article I will talk about exploratory software testing of open source software components, libraries or whole frameworks. So why would you want to do this? Think about this: the amount of hand written code in any modern application is somewhere between 3 to 10 percent of the overall byte code instructions. The rest are usually 3rd party open source libraries and frameworks used by the application such as Apache Commons or the Spring Framework.

But how do you as a software developer or architect decide which open source component to use for a certain required functionality? How do you know that this fancy framework you read about in a programming magazine suites your requirements? How do you evaluate how a library is integrated best into your application?

This is when exploratory testing of open source software comes into play. In summary, the goals of exploratory testing of open source components are:

- To gain an understanding of how the library or framework works, what its interface looks like, and what functionality it implements: The goal here is to explore the functionality of the open source component in-depth and to find new unexplored functionality.

- To force the open source software to exhibit its capabilities: This will provide evidence that the software performs the function for which it was designed and that it satisfies your requirements.

- To find bugs or analyse the performance: Exploring the edges of the open source component and hitting potential soft spots and weaknesses.

- To act as a safeguard when upgrading the library to a new version: This allows for easier maintenance of your application and its dependencies. The exploratory test detect regressions a new version might introduce.

Scenario based software exploration

If you want to use a new open source component in your project and application you usually already have a rough vision of what you expect and want to gain from its usage. So the idea of scenario based software exploration is: describe your visions and expectations in the form of usage scenarios. These scenarios are your map of the uncharted terrain of the libraries’ functionality. And the scenarios will guide you through the test process. In general, a useful scenario will do one or more of the following:

- Tell a user story and describe the requirements

- Demonstrate how a certain functionality works

- Demonstrate an integration scenario

- Describe cautions and things that could go wrong

Exploratory Testing with Spock

Of course you can write exploratory tests with more traditional xUnit frameworks like JUnit or TestNG. So why use Spock instead? I think the Spock Framework is way better suited to write exploratory tests because it supports the scenario based software exploration by its very nature:

- Specification as documentation

- Reduced, beautiful and highly expressive specification language syntax

- Support for Stubbing and Mocking

- Good integration into IDEs and build tools

The following sections will showcase these points in more detail by using Spock to write exploratory tests for the Kryo serialization library.

Specification as documentation

The good thing about Spock is that it allows to use natural language in your specification classes. Have a look at the following example. Currently it does not test anything, it is pure documentation. Even if you do not know Spock at all, I think you can understand what the test is supposed to do just by reading the specification. Awesome.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

| @Title('Exploratory test for the shallow/deep copy functionality of Kryo')

@Narrative('''

Making object copies in Java is an often required functionality.

Writing explicit copy constructors is fast but also laborious.

Instead the Java Serialization is often misused to make copies.

Kryo performs fast automatic deep and shallow copying by copying

from object to object.

''')

class KryoShallowAndDeepCopySpec extends Specification {

@Subject

def kryo = new Kryo()

def "Making a shallow copy of a semi complex POJO"() {

given: "a single semi complex POJO instance"

when: "we make a shallow copy using Kryo"

then: "the object is a copy, all nested instances are references"

}

def "Making a deep copy of a semi complex POJO construct"() {

given: "a semi complex POJO instance construct"

when: "we make a deep copy using Kryo"

then: "the object and all nested instances are copies"

}

}

|

Reduced, beatiful and highly expressive language syntax

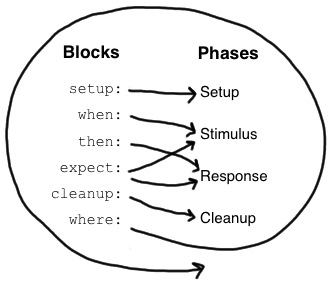

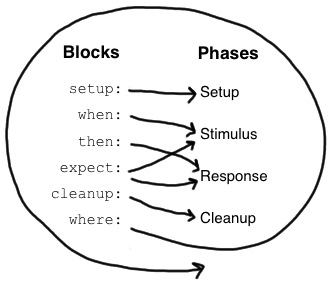

The reduced syntax offered by Spock mainly comes from its Groovy nature. Exploratory tests really benefit from this because it helps you to focus on the important bits: the open source component you want to explore. In addition to this Spock brings along its own DSL to make your specification even more expressive. Every feature method in a specification is structured into so-called blocks.

See Spock Primer for more details.

See Spock Primer for more details.

These blocks not only allow you to express the different phases of your test. By using these blocks you can demonstrate how an open source component works and how it can be integrated into your codebase. The setup: or given: block sets up the required input using classes from your application domain. The when: and then: blocks will exhibit how a certain functionality works by interacting with the test subject and asserting the desired behaviour. Again, due to the Groovy nature of Spock your assertions only need to evaluate to true or false. And for the last bit of expressiveness you can use your good old Hamcrest matchers.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

| def "Deserialize a GCustomer object from a temporary data file"() {

given: "a Kryo input for a temporary data file"

def input = new Input(new FileInputStream(temporaryFile))

when: "we deserialize the object"

def customer = kryo.readObject input, GCustomer

then: "the customer POJO is initialized correctly"

customer

expect customer, notNullValue()

customer.name == 'Mr. Spock'

expect customer.name, equalTo('Mr. Spock')

}

|

Support for Stubbing and Mocking

The Spock Framework also brings its own support for Mocks and Stubs to provide the means for interaction based testing. This testing technique focuses on the behaviour of the object under test and helps us to explore how a component interacts with its collaborators, by calling methods on them, and how this influences the component’s behavior. Being able to define mocks or stubs for every interface and almost any class also alleviates you from having to manually implement fake objects. Stubs only provide you with the ability to return predefined responses for defined interactions, whereas Mocks additionally provide you with the ability to verify the interactions.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

| def "Explore writing an object using a Serializer mock"() {

given: "a Kryo Serializer mock and dummy output"

def serializer = Mock(Serializer)

def output = new Output(new byte[1])

when: "serializing the string Mr. Spock"

kryo.writeObject(output, 'Mr. Spock', serializer)

then: "we expect 1 interaction with the serializer"

1 * serializer.write(kryo, output, 'Mr. Spock')

}

def "Explore reading an object using a Serializer stub"() {

given: "a dummy input and a Kryo Serializer stub"

def input = new Input([1] as byte[])

def serializr = Stub(Serializer)

and: "a stubbed Customer response"

serializr.read(kryo, _, GCustomer) >> new GCustomer(name: 'Mr. Spock')

when: "deserializing the input"

def customer = kryo.readObject(input, GCustomer, serializr)

then: "we get Mr. Spock again"

customer.name == 'Mr. Spock'

}

|

A good IDE and build tool integration is an important feature, since we want our exploratory tests to be an integral part of our applications’ codebase. Fortunately, the Spock support is already quite good, mainly due to the fact that Spock tests are essentially translated to JUnit tests. To get proper syntax high lighting and code completion you can install dedicated plugins for your favourite IDE. For IntelliJ there is the Spock Framework Enhancements Plugin and for Eclipse there is the Spock Plugin available.

The build tool integration is also pretty straight forward. If you are using Gradle for your build, the integration is only a matter of specifying the correct dependencies and applying the groovy plugin as shown in the follow snippet.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

| apply plugin: 'groovy'

dependencies {

// mandatory dependencies for using Spock

compile 'org.codehaus.groovy:groovy-all:2.4.1'

testCompile 'org.spockframework:spock-core:1.0-groovy-2.4'

testCompile 'junit:junit:4.12'

testCompile 'org.mockito:mockito-all:1.10.19'

// optional dependencies for using Spock

// only necessary if Hamcrest matchers are used

testCompile 'org.hamcrest:hamcrest-core:1.3'

// allows mocking of classes (in addition to interfaces)

testRuntime 'cglib:cglib-nodep:3.1'

// allows mocking of classes without default constructor

testRuntime 'org.objenesis:objenesis:2.1'

}

|

For Maven you have to do a little more than just specifying the required Spock dependencies in your POM file. Because Spock tests are written in Groovy, you will also have to include the GMavenPlus Plugin into your build so that your Spock tests get compiled. You may also have to tweak the Surefire Plugin configuration to include **/*Spec.java as valid tests.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

| <build>

<plugins>

<!-- Mandatory plugins for using Spock -->

<plugin>

<groupId>org.codehaus.gmavenplus</groupId>

<artifactId>gmavenplus-plugin</artifactId>

<version>1.4</version>

<executions>

<execution>

<goals>

<goal>compile</goal>

<goal>testCompile</goal>

</goals>

</execution>

</executions>

</plugin>

<!-- Optional plugins for using Spock -->

<plugin>

<artifactId>maven-surefire-plugin</artifactId>

<version>2.6</version>

<configuration>

<useFile>false</useFile>

<includes>

<include>**/*Spec.java</include>

<include>**/*Test.java</include>

</includes>

</configuration>

</plugin>

</plugins>

</build>

<dependencies>

<!-- Mandatory dependencies for using Spock -->

<dependency>

<groupId>org.spockframework</groupId>

<artifactId>spock-core</artifactId>

<version>1.0-groovy-2.4</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

<!-- Optional dependencies for using Spock -->

<dependency>

<groupId>org.codehaus.groovy</groupId>

<artifactId>groovy-all</artifactId>

<version>2.4.1</version>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.codehaus.groovy</groupId>

<artifactId>groovy-backports-compat23</artifactId>

<version>2.3.7</version>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>junit</groupId>

<artifactId>junit</artifactId>

<version>4.12</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.mockito</groupId>

<artifactId>mockito-all</artifactId>

<version>1.10.19</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

<!-- only required if Hamcrest matchers are used -->

<dependency>

<groupId>org.hamcrest</groupId>

<artifactId>hamcrest-core</artifactId>

<version>1.3</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

<!-- enables mocking of classes (in addition to interfaces) -->

<dependency>

<groupId>cglib</groupId>

<artifactId>cglib-nodep</artifactId>

<version>3.1</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

<!-- enables mocking of classes without default constructor -->

<dependency>

<groupId>org.objenesis</groupId>

<artifactId>objenesis</artifactId>

<version>2.1</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

</dependencies>

|

References

That’s all folks!

See Spock Primer for more details.

See Spock Primer for more details.